When I was a little girl, my mom had a Venus flytrap. We would tease it by touching its fly-eating pads with a pencil and then watch them snap shut. It was exciting to my wee eyes to see such a deliberate action by something as normally inert as a plant.

Thinking her plant needed her assistance, my mom would carefully pluck the wings off houseflies and feed them to it. When there were no flies to be had, she fed it raw hamburger, cut up in the tiniest pieces. She carefully tended it in this way for years.

I don't remember what happened to the Venus flytrap, although I guess it eventually died.

Thinking about that plant makes me nostalgic for my mom and my childhood and gave me the bright idea to procure a Venus Flytrap for my own family. I scoured the options on Amazon (where else?) and ordered one from a grower with over 900 5-star reviews. I figured it was a safe bet, and exceeded my expectations arriving with not one but four separate Venus Flytrap plants in one container.

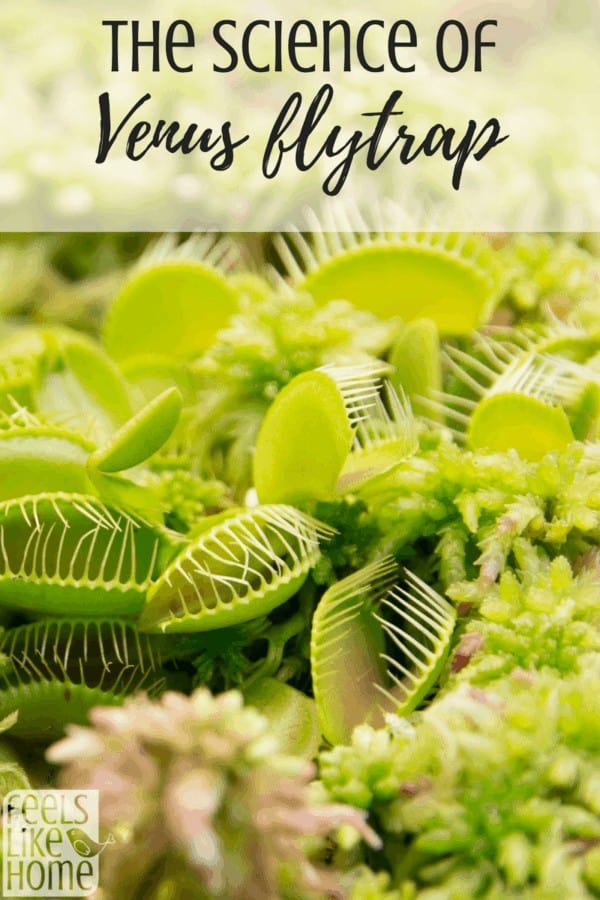

The Science of Venus Flytrap

Venus flytraps are among a small group of plants that are carnivorous or meat-eating. Also in this group are the sundew, pitcher plant, and bladderwort. These plants typically grow in poor soil conditions, necessitating additional nutrients from an outside source (bugs and other small creatures). They still get all their energy from the sun and moisture from rainfall, but their fertilizer so to speak comes from ingesting prey.

Venus flytraps are native to boggy areas in 16 counties in North and South Carolina in the United States. They are a small plant and perennial in their native habitat. This means that they die back during the winter, but the plant always comes back in warmer weather. This does not mean that they are hardy and can survive a winter north of the Carolinas, however, so definitely plan on them being a houseplant in most climates (though they can successfully go outside during northern summers).

Venus flytraps are a threatened species in their native habitat, due in large part to over-harvesting. In most places, it is illegal to take a Venus flytrap from the wild.

Venus flytraps are very long-lived plants, growing anywhere from 20 to 30 years in the right conditions. They key to achieving this long life is replicating their natural growing conditions as closely as possible, which I have described below. Many die within a couple of months of purchase because they are not given adequate airflow, have the wrong substrate (that's the moss they're growing in), or have either too much or not enough water.

The most distinctive part of a Venus flytrap, of course, is its red trap. The traps are hinged leaves with tiny hairs along the outer edges. When the hairs are disturbed, the trap snaps shut with lightning speed to catch the insect that landed inside. I have read that the traps can only shut an average of 7 times each, so it's best not to make them snap closed for fun (although we did this endlessly as kids).

According to the US Fish & Wildlife Service, the Venus flytrap actually eats very few flying insects. Instead, their diet is about 33% ants, 30% spiders, 10% beetles, and 10% grasshoppers. When you want to feed your flytrap, go outside and hunt for some ants or spiders!

How to Grow a Venus Flytrap

Here's where to buy a nice Venus flytrap.

Our Venus flytrap arrived bare root, that is, it was a mature plant (important since it can take 2-3 years to grow from seed) with roots, but its roots were bare and not potted. If you buy one that's already potted, take a careful look at the substrate.

Venus flytraps should not grow in regular old garden soil or even in potting soil. This type of soil is too dense and will eventually smother the plant's roots and kill the plant. If it doesn't come with a potting medium (mine came with Sphagnum moss), you should get some Sphagnum moss or flytrap soil specifically mixed for it. Both allow lots of air to get to the roots, providing for a healthy, thriving plant.

Venus flytraps are a flowering plant, getting a stalk of white flowers usually once a year. Don't worry if this happens - it doesn't mean that your plant is dying. The stalk will grow, it will make flowers, the flowers will make seeds (which you can plant if you want to grow new plants), and then the flowers and stalk will die back. The only caveat to flowering is that the flowers do take nutrients that could otherwise be used to produce new traps. If you value new traps over flowers, pinch the stalk off before the flowers form.

Never, ever fertilize a Venus flytrap! They get all the nutrients they need from their prey.

Venus flytraps like a lot of bright light although they don't want direct sunlight in the summer (it can get too hot). I have ours under this grow light which I got last year and love. It makes bright pink light that never gets hot. You can keep it pretty close to your plant - as close as 2 inches from the leaves - and it won't hurt the plant.

Venus flytraps need adequate air circulation, so closed terrariums are a bad idea (even though they are often sold in these in the stores). The bulbs also can't sit in standing water but do require an evenly moist root environment. You'll want to keep the pot in a dish of water and water frequently with rain water but again, no standing water at the height of the bulbs (no deeper than ¼ up the pot). If you aren't into collecting rain water, get a jug of distilled water. It's about 80¢ a gallon and will make your plant a lot healthier. I actually poach Joe's distilled water that he keeps for his CPAP machine. Tap water can kill your Venus flytrap because it generally has a higher pH (alkaline as opposed to neutral or acidic) and contains a lot of dissolved minerals.

You should feed your Venus flytrap, although you don't have to do it the way my mom did. The key is that the insect must be alive when the plant eats it. (Gross, I know.) If it is dead and not squirming, the trap won't always snap shut.

On the other hand, if you have flies in the house, you may not need to feed your flytrap at all. Keep an eye on it, watching to see if any of the traps are shut and lumpy.

Your Venus flytrap can eat as much as every week or as infrequently as once a month, so if you drop an ant or spider onto one of the traps every other or every third week, it will be in great shape and get all it needs.

According to that Amazon grower, Venus flytraps will grow just fine even if they never, ever eat. They will grow slowly, but they will still grow.

Venus flytraps need a period of winter rest like many perennials. Most of the leaves should die back, but don't fear - your plant isn't dead. Store it somewhere that's around 50 degrees, maybe a basement or close to an outside window, but don't let it get too cold. If it freezes, it will die. Continue to water and keep it in a sunny window. Around the end of February, bring it back into a warmer environment. It will perk up and grow new leaves.

If your Venus flytrap doesn't die back in the fall, force it. Put it in a cool place from October until the end of February, and then bring it out. As above, continue watering and keep it in a sunny window. If it doesn't go dormant for at least a couple of months, it will eventually peter out and die.

Feeding versus fertilizing - It's really a mistake to say that we're "feeding" our flytraps. All plants, including carnivorous ones, make their own food using photosynthesis. They use sunlight to make sugar which feeds the plant and provides it energy to work its cells and functions. What we are doing here is providing our plants with the nutrients that they need, specifically nitrogen. In people, getting energy and nutrients happen at the same time, so this point can be confusing for kids.

Venus Flytrap Experiments for Kids

Here's where to buy a nice Venus flytrap.

Experiment design

Any good experiment needs 3 parts - the independent variable, the dependent variables, and the controls.

The independent variable is the thing that you change. It could be the type of food, the frequency of feedings, or the place you touch on the leaves. The dependent variables are the things that are determined by what you do. So in the case of the type of food, the dependent variables would be the size and overall health of the plant. In the case of touching the leaves, the dependent variable would be the behavior of the traps (do they snap shut or not?). The controls are the things that stay the same for all trials. A good experiment has as many controls as possible. For the different types of food, your controls would be that all the plants are treated exactly the same - same light source, same distance to light, same watering schedule. For the touching experiment, the control would be that you're touching the same plant each time.

Venus Flytrap Experiments

In almost every case, you should include a normal, healthy plant in your experiment. This plant should not get any treatments at all, just the same sunlight and watering that the other plants get. No extra food beyond what it catches on its own, no crazy touching, etc.

Digestion - This isn't so much an experiment as an explanation. The flytrap's traps work just like our mouths. When the trap closes, it secretes enzymes that break down the food. Our mouths work the same way. You can demonstrate this to your kiddos using cotton candy. Have them put a hunk of cotton candy in their mouths and close their mouths. Now, don't chew or do anything. The cotton candy eventually disappears because the enzymes in their mouths break it down. (Okay, full disclosure, the heat and moisture in their mouths also play a part, but the important thing to highlight here is the digestive enzymes.)

Snapping the traps shut - I know I said above not to tease the plant, but it is an interesting experiment to touch the leaves once or twice and watch them snap shut. You could extend this by touching various parts of the traps and leaves. Do they snap shut when you touch just the hairs? How about the inside of the trap and not the hairs? What if you touch only one hair and not multiple? What if you disturb the non-trap leaves? Experiment by touching various parts of the plant in different ways.

Opening traps - Depending on what is inside the trap, it may open in as little as 12 hours or it may stay shut for days. Watch for this to happen and record the results. Does it matter whether the trap had an insect or hamburger inside, for example?

Cut traps - I wouldn't be able to do this one because it would make me sad to cut a trap off of my plant. But if you could, it would be really interesting to see whether the trap still closes and behaves the same way after it's been cut from the plant.

Effect of sunlight on traps - This one is an extension of the above. You would expose 3 plants to differing amounts of sunlight. Perhaps one would be under a grow light, one would be in a sunny window, and the third in the center of the room in a lower light scenario. Then time with a stopwatch the number of seconds or milliseconds it takes for the trap to shut when disturbed. Does the amount of sunlight matter?

Dead insects - It's also interesting to put a dead fly or bug into the leaves and see what happens. You may be able to get the trap to shut by touching the hairs, but wait to see what happens when the trap opens up again - is the dead bug digested and gone or is it still there? I'll leave that for you to discover.

Vary its diet - Get 3 different Venus flytraps and feed each one different foods. One could get all live insects. The others could get cooked or raw hamburger meat, cooked or raw chicken, cat or dog food, . Measure the amount of growth and the overall health of the plants, but make sure they are treated exactly the same aside from the feeding. Same distance to the light source, same amount of watering, same potting material.

Frequency of feedings - Again with 2 or 3 different plants, you would feed one weekly, one biweekly, and one monthly. Measure the overall growth of the plants and the overall health. I think this one would be especially interesting because you may find that it doesn't make a difference, which would lead me to think that more frequent feedings just get wasted. I'm not sure, though. It would be an interesting experiment.

Various growing conditions - Venus flytraps are pretty expensive plants and not all that hardy, so I don't know if you'll want to do this, but I thought I should at least mention it. You could vary the conditions in which you keep the plants. One could get water weekly, another twice a week. Or one could get direct sunlight in a window and another via a grow light. As with the diet, you could measure the overall growth and health of the plants.

**A note on measuring growth - It can take up to 4-6 months for a Venus flytrap to show any growth changes in response to the food you're feeding. If you decide to do one of the above experiments, be prepared to watch it in the longterm. You won't see results in a couple of weeks.

Books About Carnivorous Plants

There are loads of books about carnivorous plants to help your kids understand and appreciate them.

My favorite is Plantzilla which is fiction, about a little boy who cares for Plantzilla for the summer. It is an amazing story that Allie and I LOVED reading together. Instead of regular prose, it is written in letters from the little boy to his teacher, from his mother to his teacher, and from the teacher to the family. It's really interesting to see the growth of Plantzilla of the course of the summer and how he becomes a member of the Henryson family. Love love love this book.

There's another really good book called Hungry Plants which is non-fiction and also very good. It's about all types of carnivorous plants, not just Venus flytraps.

Find more book-inspired science activities at Storybook Science going on now at Inspiration Laboratories!

The End

All this to say that Venus flytraps can be pretty hard to grow and keep healthy, but I think they are worth it to at least try. They're fun plants when grown under ideal conditions, and your kids will love watching them snap shut around insects.

Trisha says

We read a book called Meat Eating Plants a few years ago. It prompted my son to request a Venus Flytrap of his own. We found one at Home Depot. It didn't survive very long. Now I know why! Maybe we'll try again. They are very cool plants.

Tara Ziegmont says

Yes they are! I've had mine from the grower I linked for a couple of weeks, and it's still going strong.